Introduction

Henry Ford grew up near Dearborn, Michigan, reconstructing and repairing mechanical devices. At the age of 16, he found work and learning opportunities at the Michigan Car Company Works.

In 1907, Henry Ford vowed to make "a motor car for the great multitude" rather than a luxury item for the rich. He would accomplish this by bringing down the price and producing large quantities to achieve economies of scale.

Who was Henry Ford, and what was the first vehicle he ever built? How did he come to revolutionize the automobile industry?

Fascination

The son of Irish immigrants, Henry Ford was born on July 30, 1863, in the area of Dearborn, Michigan, to a prosperous farming family headed by William and Mary (Litogot) Ford. He was the eldest of six surviving children. Taught to read by his mother before attending a one-room school, Henry grew up reconstructing and repairing mechanical devices and, as a teenager, was instantly fascinated by steam-driven engines. That fascination grew into a lifetime of engineering involvement and business success.

Unsuited to farming life, he later observed "my earliest recollection is that, considering the results, there was too much work on the place." Ford, then sixteen years old, walked the eight miles to Detroit and found work and learning opportunities at the Michigan Car Company Works. He moved on to a machinist apprenticeship, then to work in the shipbuilding industry, and then in 1882, came back to the farm to operate and repair steam engines made by the Westinghouse Company.

Ford met Clara Bryant, daughter of a farmer, in the social circle of the neighborhood and on April 11, 1888, they were married and settled in a new home on the Ford farmstead. Their only child, Edsel Bryant Ford, was born in 1893.

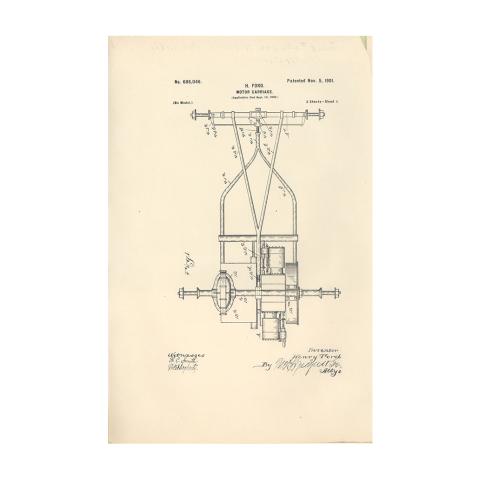

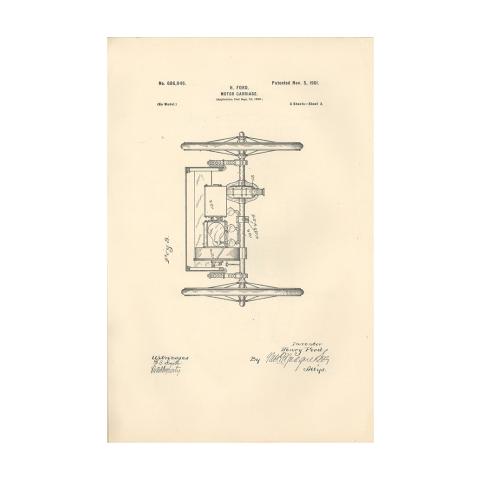

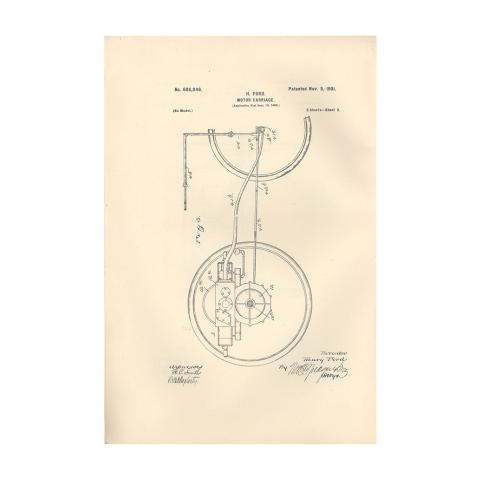

Quadricycle

In 1891, Ford left the farm again, this time for work at the Edison Illuminating Company in Detroit as a night engineer. In his spare time at the Edison Illuminating Power plant and in his Detroit apartment, he switched his attention and began building experimental gasoline-powered engines. The first Ford vehicle, the "Quadricycle," an improvement on previous gasoline-powered vehicles, resulted from this work and was built in the June of 1896 in a nearby garage.

The Quadricycle consisted of a toolbox seat mounted on a chassis, in front of the engine which powered the four bicycle wheels via 10 feet of bicycle chain. Its two-cylinder engine generated four horsepower and a top speed of 20 mph. It had no brakes and no reverse gear drive and it "stopped" by breaking down on its maiden trip through Detroit.

Ford's enthusiasm endured and he was encouraged by the support of Thomas Edison who now favored the gasoline-powered over the electric-powered version of the horseless carriage.

A second Ford model followed in 1898 and by August of the following year, Ford obtained sufficient financial backing to resign from Edison and become superintendent of the new Detroit Automobile Company. This enterprise lasted just one year, beaten by the conflict between rapid profit and the hopes of backers versus output capabilities. One successful model, a delivery wagon, was manufactured in that time.

The Race

Next, Ford, maintaining some financial backing, turned his attention to establishing his name in the automobile industry by developing racing engines. His lightweight, two-cylinder engines defeated the high-powered, and correspondingly heavier, four-cylinder models; in 1902, it began to win him prizes and recognition in races staged in Detroit. As Ford continued developing more powerful racing cars, his supporters, preferring the prospects for lightweight all-purpose vehicles, left to reorganize and establish the Cadillac Automobile Company.

Racing bicyclists were Ford's next partners; they had the funds and the nerve to drive machines that developed up to 80 horsepower and 60 miles per hour. Tom Cooper and Barney Oldfield joined the team. Oldfield, soon to become a racing legend, won prizes with the 1902 Ford 999, while Henry Ford himself drove the Ford Arrow to a world land speed record of 91.37 mph in 1904.

Industrial Community

With his reputation established, Ford's interest turned to lightweight conventional automobiles and he partnered with Alexander Malcomson, a Detroit coal dealer. In 1903, their company, the Ford Motor Company, embarked on the mass assembly of runabout automobiles—all parts of production being contracted out to a variety of suppliers. They became part of a Detroit-based industrial community that included such companies as Olds, Dodge, and Cadillac.

At its inception, the company had around $50,000 in capital and twelve stockholders. The company survived some difficult circumstances such as insufficient funds, slow stock sales, and bank bailouts. However, by the end of the year had achieved net profits of over $36,000 and expanded rapidly.

In His Favor

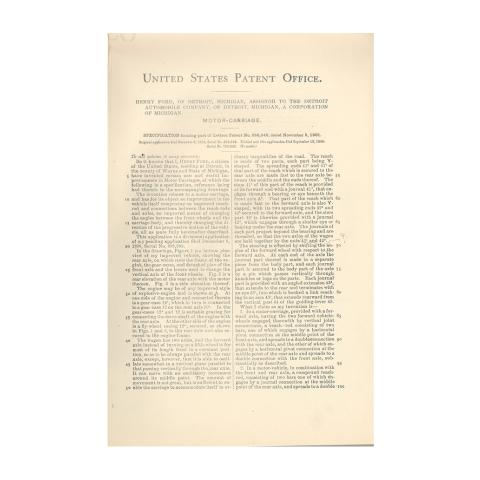

Once successful, Henry Ford became the target of the Association of Licensed Automobile Manufacturers. The Association had acquired the rights to an automobile patent applied for and obtained over a period of 25 years by inventor and patent attorney, George Baldwin Selden, and was collecting a licensing fee for each vehicle manufactured by the Oldsmobile and Cadillac companies. Now Ford was denied membership of the Association for "business unreliability" and further, a lawsuit was brought against Ford for patent infringement.

The lawsuit lasted almost six years with the final judgment that the Selden patent was valid. Ford immediately appealed the verdict and the appeals court reversed the decision in his favor on January 9, 1911. The Association of Licensed Automobile Manufacturers did not appeal the reversal and Henry Ford was a national hero.

Wider Pursuits

The Model T Ford had been introduced in 1908 and, as Henry Ford advanced his mass production methods, 15 million cars were sold before this model was discontinued in 1927 and production switched to the Model A. Reflecting this success, the original Highland Park factory was replaced by the huge Rouge River plant in 1917. The company shareholders resisted this diversion of funds to plant expansion and their resulting lawsuit against Henry Ford was judged valid (by 1920, in his authoritarian fashion, Henry Ford had bought out these shareholders).

During this period, with the plant functioning well and his son, Edsel, now president of the company, Ford ceded some control and turned his attention to wider pursuits. His pacifist stance during World War I caused his brilliant original partner, James Couzens, to leave the company and his suppliers, the Dodge Brothers, ended their arrangement and began their own car manufacturing company.

In 1915, Ford financed a well-publicized peace ship, the Oscar II, which sailed to neutral European countries in an effort to end hostilities by “continuous mediation”, which failed to prevent the United States from joining the combat in 1917. In 1918, he purchased The Dearborn Independent and used it to publish attacks blaming the mythical "International Jew" for financing wars. He later retracted these comments in 1927. President Woodrow Wilson encouraged Ford's candidacy for the United States Senate in 1918, but his opponent's personal attacks led to his defeat.

Ford and Edsel created the philanthropic Ford Foundation in 1936 to “strengthen democratic values, reduce poverty and injustice, promote international cooperation and advance human achievement”.

Union Relations

Ford's strong opinions on benevolent labor relations (he increased his workers' minimum wage from $2.83 per 9-hour day to $5.00 per 8-hour day in 1914 while establishing some living style requirements of decency) did not extend to acceptance of the 1935 Wagner Act establishing trade union rights. He refused to join Chrysler and General Motors in their post-strike agreements with the United Automobile Workers Union (UAW), instead using company enforcers and spies to discourage unionization in his plant. The 1937 "Battle of the Overpass", in which the enforcers attacked and severely injured canvassing union representatives, marked a historic moment in labor history. Ford was censured by the National Labor Relations Board despite their denials. In 1941, Ford Motor Company finalized a contract with the UAW.

In 1943, Edsel Ford died of cancer at the age of 49 and his father resumed total control of the company. He died four years later of a cerebral hemorrhage at the age of 83.

Mass Production

In the beginning, automobiles were built by craftsmen who assembled the finished vehicle from parts they themselves had made, making any necessary adjustments to these parts as they went along. On the road to mass production, many improvements were made that sped up the process and optimized the use of skilled labor.

The quality and uniformity of interchangeable engine parts was standardized. The use of machine tools and templates in parts production was introduced, permitting the use of less skilled workers and separating that contribution from the main assembly operation. Ford minimized labor turnover and ensured an eventual market for his cars with introduction of generous wages and hours for workers who matched his requirements.

Companies that specialized in manufacturing only certain parts grew, giving further meaning to the assembly process which now spread to include a variety of specialty suppliers. The first assembly line for mass production of automobiles was set up by Ransom E. Olds for the Olds Motor Works in 1901. 600 models of his Curved Dash Oldsmobile were sold in that year, rising to 5,000 in 1904.

Motor Cars

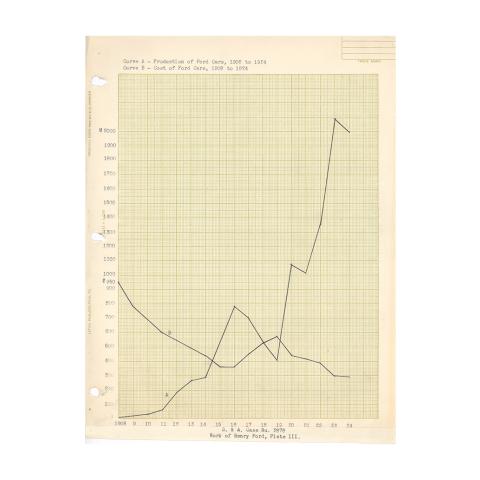

Meanwhile, Henry Ford entered the automobile manufacturing business in 1903 and by 1907 had vowed to make "a motor car for the great multitude" rather than a luxury item for the rich. He would accomplish this by bringing down the price and producing large quantities to achieve economies of scale.

A series of models and prototypes, labeled alphabetically A through S, were produced by the Ford Motor Company from 1903 to 1908. Production of the Model T, his most successful model, began in 1908.

Scientific Management

At that time, Frederick Winslow Taylor, a professor at Dartmouth College, was developing his Principles of Scientific Management, which included the timed study of individual operations in a complex task. Combined with motion study, these methods used close examination of the task, classification of the distinct movements made by the worker involved, and analysis for streamlining the task, thereby increasing efficiency.

Henry Ford incorporated this information and technical research in the team he established to develop a manufacturing system that could mass produce the affordable Model T that he designed to be easy to drive and repair.

First came analysis of the components list for the automobile: from the smallest coupling to the main chassis. It was first decided that the larger, heavier parts, such as axles and engines, would be in a fixed area while the smaller parts were stored elsewhere and delivered in batches as required for assembly. The next advance was the decision to build the basic chassis (wheels, axles and frame), then move it through the storage areas, adding to the assembly in stages. Finally, after much trial and error and a few missteps followed by detailed analysis, a layout of the entire assembly parts and sequence was made ready for practical experimentation. Movement along the line was provided by hand towing the chassis on a sled through the production stages to the point where the wheels were added.

93 Minutes

Once in place and scrutinized, the demonstration line showed the need for further adjustments. Some assembly stages took longer than expected so parts supply rates along the line were changed. Entire sub-assemblies of such components as radiators, dashboards, and steering mechanisms were set up so that they could be incorporated in the main line production.

The moving assembly line plan was developed over a five-year period and finally put into operation when the new Highland Park, Michigan factory was opened by Ford in 1913. There, a fully-synchronized, power-driven line began with engine assembly on the fourth floor and ended on the ground floor with the body being attached to the chassis. Workers at each station handled one specific repetitive step contributing a small part of the eventual whole. In time, Ford integrated the entire process with the raw materials—coal fuel, ore, and wood—entering the plant and the finished automobiles coming out. By 1914, the entire assembly process took 93 minutes.

From 1908 through 1927, more than 15 million Model T’s were manufactured and their price declined from $850 to $300. Ford dealerships were set up throughout the United States and in Europe, Ford Motor Company was an outstanding success and the assembly line principle spread to countless manufacturing operations.

Acknowledgement

Henry Ford was awarded The Franklin Institute's 1928 Cresson Medal in Engineering for revolutionizing the auto industry and industrial leadership.

Credits

The Henry Ford presentation is made possible by support from The Barra Foundation and Unisys.

This website is the effort of an in-house special project team at The Franklin Institute, working under the direction of Carol Parssinen, Senior Vice-President for the Center for Innovation in Science Learning, and Bo Hammer, Vice-President for The Franklin Center.

Special project team members from the Educational Technology department are:

Karen Elinich, Barbara Holberg, Margaret Ennis, and Zach Williams.

Special project team members from the Curatorial department are:

John Alviti.

The project's Advisory Board Members are:

Ruth Schwartz-Cowan, Leonard Rosenfeld, Nathan Ensmenger, and Susan Yoon.