Introduction

Every filmmaker—from D.W. Griffith to Steven Spielberg—owes a debt of gratitude to C. Francis Jenkins, perhaps the least known inventor of his generation. Jenkins' legacy, however, is vast; His technologies gave rise to the motion picture industry that still captures our imaginations today.

Who was C. Francis Jenkins? What was the Phantoscope apparatus, and what did Jenkins contribute to motion pictures?

Early Life

Charles Francis Jenkins was born to Quaker parents in 1868 just north of Dayton, Ohio, and grew up on a farm near Richmond, Indiana. He went to country school, high school, and then to Earlham College. Jenkins left for Washington, D.C. in 1890 where he worked as a secretary at the U.S Life Saving Service. A year later, he began experimenting with movie film, and concentrated on developing the Phantoscope, his own prototype of the motion picture projector.

Jenkins claimed to stage the first "movie" show in 1894 at a jewelry store in Richmond, Indiana, that was owned by his cousin, Charles. Jenkins had his motion picture projector shipped from Washington to Richmond. He projected pictures of a dancer performing a "butterfly dance" onto the wall. Today, there is a plaque outside that building at 726 Main commemorating the event.

In 1895, Jenkins quit his job to pursue invention as a full-time profession.

A Partnership

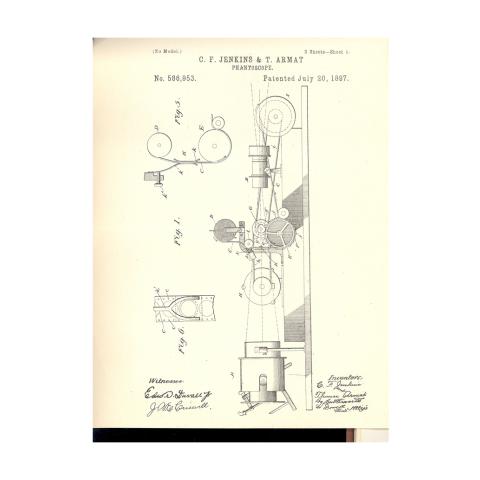

Jenkins attended the Bliss School of Electricity in Washington, D.C., where he met classmate Thomas Armat. With Armat acting as financier, the pair worked on and improved upon the design of the Phantoscope projector.

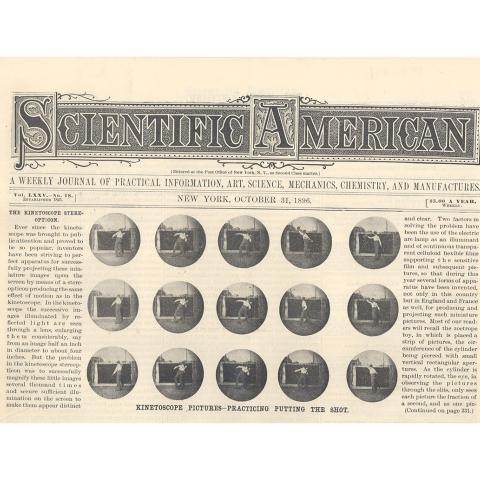

In the late nineteenth century, public fairs and expositions were an important way for cities to attract visitors. People were eager to see new technological developments on display. Atlanta hosted three such expositions in the years following the Civil War, meant to help foster recovery and economic development for the city. Jenkins and Armat held a public screening at the last of the three, in the fall of 1895 at the Cotton States and International Exposition, projecting Kinetoscope films with the Phantoscope. (The Kinetoscope had been invented in the late 1800s, and was a device that gave the impression of movement by moving a loop of film continuously over a light source with a rapid shutter.)

Jenkins and Armat split soon after the Exposition, with each party claiming the invention to be their own effort. The two worked independently on improving the Phantoscope.

Display and Dispute

By mid-December of 1895, Jenkins had his version of the device ready, and demonstrated moving pictures with the projector to a distinguished audience at The Franklin Institute Science Museum in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

In a letter written to Chairman of the Committee on Science and the Arts H.R. Heyl in August of 1897, Jenkins provides information relative to his "claim of priority of invention" of the Phantoscope. Jenkins asserted that he was advised by the pair's joint attorneys to file a patent as sole inventor of the Phantoscope (a joint application had already been filed). To his surprise, he learned this was not agreeable to Armat. "Interference proceedings" were declared, and carried out for several months. Armat subsequently notified Jenkins that he had sold all of the rights, title, and interest covered by the contract between them to his cousin and business partner, T. Cushing Daniel.

Weeks after the transaction was completed, Daniel approached Jenkins, telling him that the Armats (Thomas and his brothers) would pay cash if Jenkins withdrew the interference patent. Terms were agreed upon, and Jenkins withdrew his opposition to the joint patent application. Jenkins points out that "As the interference proceedings were abandoned, sole invention can only be inferred from a decision of Associate Justice Hagner, Supreme Court D.C., in a bill for an injunction of my use of the Phantoscope."

Upon perfecting his own version of the Phantoscope, Armat approached Raff and Gammon, who were two very prominent entrepreneurs. They were excited by what they saw and approached Thomas Edison with the intention that he further develop the projector. Edison agreed. Armat sold Edison the rights to market the Armat projecting Phantoscope under a new name, the Vitascope.

Many years later, a dispute arose concerning Armat's protest that Jenkins was not the actual inventor of the Phantoscope.

The Phantoscope Dispute

On November 14, 1924, many years after C. Francis Jenkins had been awarded the 1897 Elliott Cresson Medal and the 1913 Scott Medal for his inventions in motion picture apparatus, his former partner, Thomas Armat, wrote to The Franklin Institute requesting copies of his own correspondence with them between January and October 1898. He also asked for "any paper or report showing just what the Elliott Cresson medal was granted to Jenkins for."

The 1898 correspondence had concerned Armat's protest that Jenkins was not the actual inventor of the Phantoscope. The Institute's investigation carried out at that time had confirmed the validity of the award. Armat's complaint was dismissed.

In reply to the new request, Armat was told that Jenkin's approval would be needed to release information from the case file on his award. Jenkins refused to authorize the copying, and the matter was considered closed.

One week later, in December 1924, a letter was received from Thomas Edison telling The Franklin Institute that he had learned of the award and was requesting official confirmation and details of the award's language. The response was the same as that given Armat—Jenkins authorization was required and, in view of recent experience, was unlikely to be forthcoming.

After a month had passed, the President of The Franklin Institute received a "Personal & Confidential" letter from Samuel Insull, President of Commonwealth Edison Company in Chicago, asking that the 1897 case be re-opened. Thomas Edison's instructions were that Insull raise the matter of "a man by the name of Mr. C. Francis Jenkins" honored as the original Phantoscope inventor and the consequent "gross injustice" done to Edison himself.

The correspondence resumed six months later when Insull informed The Franklin Institute that he was turning the matter of the "alleged inventor" over to Mr. Frank Dyer, Edison's patent attorney.

Mr. Dyer met with Dr. Howard McClenahan, Secretary of the Institute, and Dr. George A. Hoadley, Secretary of the Committee on Science and the Arts, the department responsible for the medal awards.

Dyer's description to Eglin of his meeting with the Institute staff and his review of the case stated that:

Thomas Armat was the true inventor and patent holder and, in his opinion, Jenkins was guilty of "fraud and misrepresentation,"

The committee improperly denied Armat a personal hearing at the time he protested,

The Institute's affirmation of Jenkins' award perpetuated his reputation and ignored the work of Thomas Edison, resulting in misrepresentations in textbooks, the Encyclopedia Britannica, and the National Museum (Smithsonian),

The matter must be corrected since the Institute's reputation and the "grave injustice" done to Armat and Edison was at stake,

There was a member of the original awards committee, Mr. Francis R. Wadleigh, whom Dyer could contact with a view to re-opening the case.

At their meeting in Philadelphia, Hoadley had explained to Dyer the committee rules that (1) the protest period for an award is the first three months that the announcement is published in the Journal of The Franklin Institute, and (2) a case may only be re-opened at the request of a committee member to the chairman.

Subsequent developments included Dyer's notification that the report by Dr. Walter Runge, Wadleigh's approved surrogate, says that the medal was awarded under "probable conditions of fraud and misrepresentation" and Hoadley's obtaining a copy of the judgment made by Justice Hagner of the Washington D.C. Supreme Court in the 1898 case of Daniel vs. Jenkins. The case involved a suit brought on behalf of the Armat brothers for an injunction against Jenkins' manufacture and use of the Phantoscope.

The special committee investigating Dyer's claims and requests consisted of McClenahan, Hoadley, and Harold Calvert, then chairman of the Committee on Science and the Arts. Their opinion, based on the file documents from Armat's original protest and the court judgment, was that the award was justly given and no further action was required. Mr. Dyer was informed of the result.

A package of 16 items was soon received from Frank Dyer. In a December 22, 1925, letter, after receiving these items, Hoadley spelled out the reasons for the committee's continued rejection of the protest after examining all evidence:

The agreement between Armat and Jenkins concerning the Phantoscope clearly states that Armat will supply the funds and indicates, without explicitly stating, that Jenkins is the inventor.

Justice Hagner's opinion in overruling the application for an injunction refers to the May, 1896, publication in "The Photographic Times" of Jenkins' description of his invention. This account pre-dates their agreement. Also included is the judge's opinion, from reading their contract, that Jenkins was the acknowledged ideas man—the inventor.

Moving On

C. Francis Jenkins began working in television. He published an article in the September 27, 1913 issue of Moving Picture Newsentitled "Motion Pictures by Wireless - Wonderful possibilities of Motion Picture Progress," but it wasn't until ten years later that he transmitted the earliest moving silhouette images for an audience. Jenkins developed a mechanism for viewing distant scenes by radio, or—as we now know it—television.

In June of 1925, Jenkins publicly demonstrated the synchronized wireless transmission of television images. He filed for a patent on March 13, 1922, and was granted U.S. patent No. 1,544,156 for Transmitting Pictures over Wireless on June 30, 1925.

Jenkins' business endeavors included Charles Jenkins Laboratories and Jenkins Television Corporation. The latter was founded in 1928, the very same year the first commercial television license in the U.S. was granted to the Laboratories. Jenkins Television Corporation opened W3XK, the first television broadcasting station in the United States. The station was first broadcast on July 2 from the Jenkins Laboratories in Washington, D.C. Initially, due to narrow bandwidth (10kHz), W3XK was only capable of sending silhouette images. That was soon remedied—the station was allowed to move its carrier frequency to 4.95 MHz with a bandwidth of 100 kHz and a power of 5,000 Watts—so that real black-and-white images could be transmitted.

In 1931, Lee de Forest, a 20th century inventor who was responsible for creating the vacuum tube and motion picture sound, acquired Jenkins Television Corporation.

Important Contributions

Although Jenkins used mechanical rather than electronic technologies and is one of the lesser-known pioneers of television, his contributions were still of great importance. He acquired over 400 patents in his lifetime, in such diverse areas as paper containers, automobiles, propellers, and time-lapse photography. Seventy-five of those patents were dedicated to mechanical television alone. Jenkins was the founding member and first president of the Society of Motion Picture Engineers, now the Society of Motion Picture and Television Engineers (SMPTE).

C. Francis Jenkins died in June of 1934.

Eye to Brain Connection

The human eye-to-brain connection processes rapid, sequential images into a constant motion effect, with imperceptible flicker, at a threshold of around 15 images per second. The brain's impression of a static image is ten times stronger than its impression of movement. Successfully smooth motion picture projection matches these limits of the eye in image speed and persistence of vision.

Jenkins' first camera/projector, a hand-cranked machine, simply passed the unexposed film from reel to reel and the film was exposed through a fixed aperture and a lens arrangement. To view the positive film, the system was simply reversed with an arc lamp placed behind the film, the reels set in motion at the same speed as the original recording, and the image viewed through the aperture or projected onto a small screen.

Life-Size Images

The Jenkins Phantoscope corrected shortcomings in the camera/projector, providing a brighter image through an intermittent movement device which caused each film frame to "hesitate" at the picture aperture gate, and avoidance of film breakage with a pulley scheme to reduce tension in the film travel. The projector was powered by an electric motor and the shafts and pulleys design via cogs and gears operated in complete coordination.

In operation, the film is drawn, at constant speed, over an intermediate pulley and through the spring tension gate. At each revolution of the eccentric roller disk, the individual picture frame is held stationary in the gate for a short interval and then moved on. The movement is speedy—25 frames per second—so the sequential effect is smooth and the illumination is maximized. A sprocket pulley takes up the slackened film loop from the gate and it passes to the winding reel.

The Phantoscope was the first projector to produce life-size images on screens.

Acknowledgement

Charles Francis Jenkins was awarded the Elliott Cresson Medal in Invention by The Franklin Institute in 1897 for the Phantoscope projector. He later was given the Scott Medal in Invention (1913) for his Motion Picture Apparatus.

Credits

The C. Francis Jenkins presentation was made possible by support from The Barra Foundation and Unisys.

Read the Committee on Science and the Arts Report on Francis Jenkins’ invention, the Phantoscope.