Date:

Update: On February 11, The World Health Organization announced that the official name of the disease caused by the coronavirus is COVID-19, combining “coronavirus,” “disease,” and 2019–the year the virus emerged. The current reference name for the virus itself is severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2). The original post has been updated with the new nomenclature.

The death toll from a novel coronavirus—known as SARS-CoV-2—has now surpassed that of the SARS epidemic back in 2002-03. Though the current epidemic is centered in China, I saw signs of awareness and concern as I was traveling in the U.S. last week: news updates popping up on my phone, people wearing face masks in airports, and lots of reminders about hand washing in public places. We live in a world where both information and infectious disease travels fast.

What’s a coronavirus and where did this one come from?

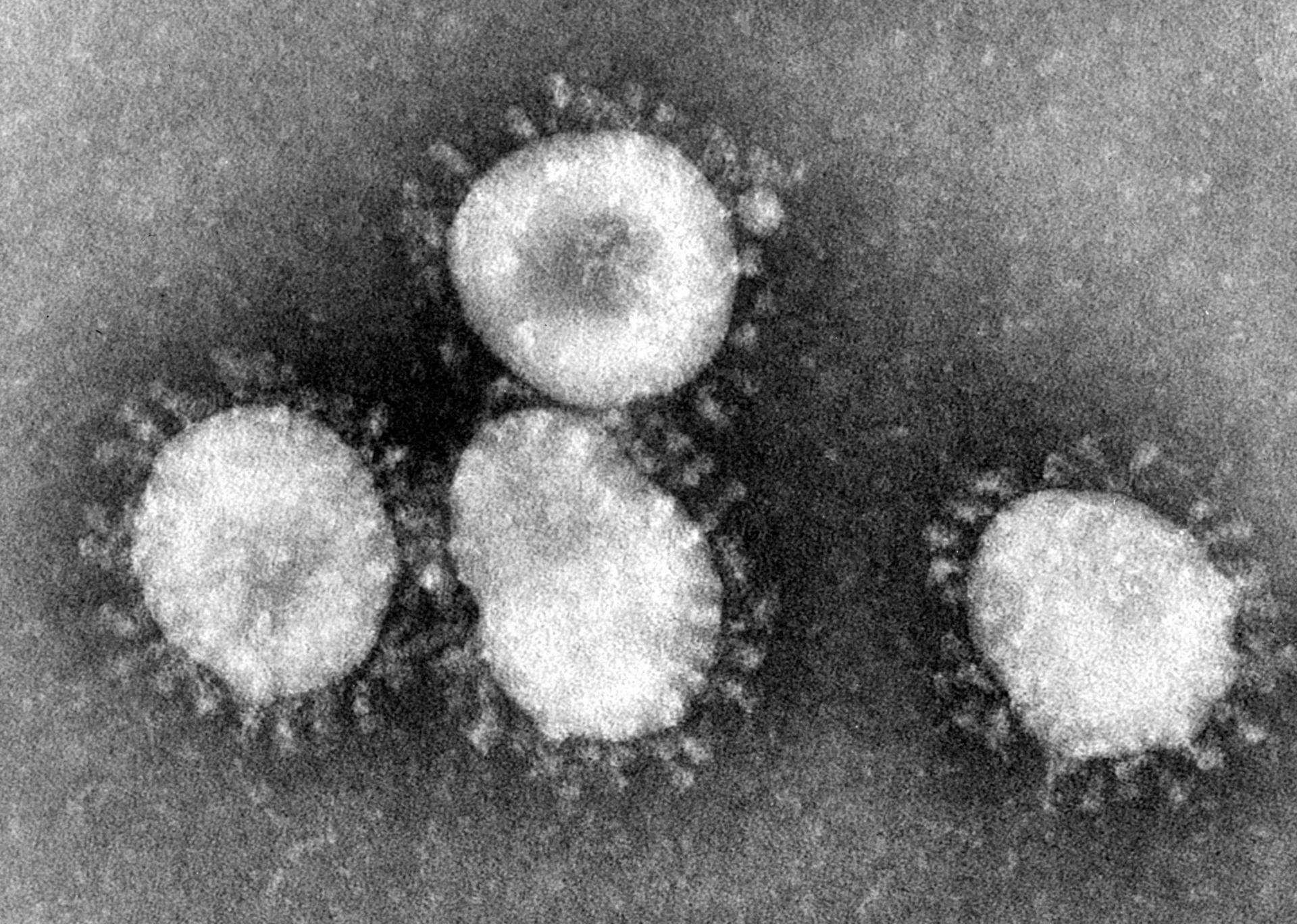

Image credit: CDC/Dr. Fred Murphy (source)

Coronaviruses are a family of viruses (including the common cold) usually made up of a single strand of RNA. They’re packaged in a capsule with spiky proteins on the surface, which help the virus infect its host cell. These proteins look like a crown—or corona, in Latin—under a microscope.

Genetic analysis has shown that many coronaviruses originate in animals, especially bats. Chinese researchers have announced preliminary findings suggesting that SARS-CoV-2 may have first jumped from bats to pangolins, scaly mammals used in traditional Chinese medicine, before infecting humans in an animal market in Wuhan, China. If confirmed, the results will help us understand how to prevent cross-species infections in the future.

Image credit: Wildlife Alliance (source)

How does it spread from one person to another?

At the moment, we don’t fully understand all the ways the virus is transmitted. Like other coronaviruses, the most likely route is through droplets from a cough or a sneeze that directly land on or are inhaled by another person. Related coronaviruses can survive on surfaces like a door handle for up to 9 days, so SARS-CoV-2 could be transmitted through surface contact. In addition, a new study suggests that the virus may also spread through feces from patients with diarrhea. Scientists are not yet sure whether the virus can spread directly through the air. Still, these multiple modes of transmission make hospital infections a particular concern.

How serious are the symptoms?

Many people have relatively mild respiratory symptoms, like fever, cough, and shortness of breath. The problem is that these mild cases make the epidemic worse, as many infected people continue to go about their lives, shedding the virus as they move. Vulnerable people, especially older adults and those with other medical conditions, are then at risk of developing much more severe symptoms now referred to as COVID-19. Though more than 900 people have died, it’s hard to estimate the mortality rate of the disease at this point—we just don’t have reliable data about the number of people infected, nor has enough time passed to follow the full progression of the disease.

How do we stop its spread?

Global and U.S. health organizations have declared the outbreak a public health emergency. What does that mean? This status is intended to release government resources, facilitate communication, and authorize additional personnel to respond to a critical situation. As cases of COVID-19 appear outside China, the hope is that a coordinated international response will at least slow its spread.

A number of research teams—including Inovio, a pharmaceutical company based in the Philadelphia region—are accelerating their development of potential drugs and vaccines, jump-started by prior work on other coronaviruses. But going from basic research to safety testing to mass production will take time.

The good news is that the same personal hygiene practices that protect us from colds and flu viruses that we commonly encounter here in the U.S. will also protect us from SARS-CoV-2. If you’re generally healthy, you don’t need a face mask. Keep your distance from people showing any symptoms, cover your coughs and sneezes, use a disinfectant to clean surfaces you touch regularly, and wash your hands with soap and water thoroughly.

With so much uncertainty, it’s still too early to predict what the global impact of SARS-CoV-2 will be. We’ll be following the situation here at The Franklin Institute, so if you’re visiting, stop by Random Acts of Science to test your sneeze protection skills and get the latest news.