Introduction

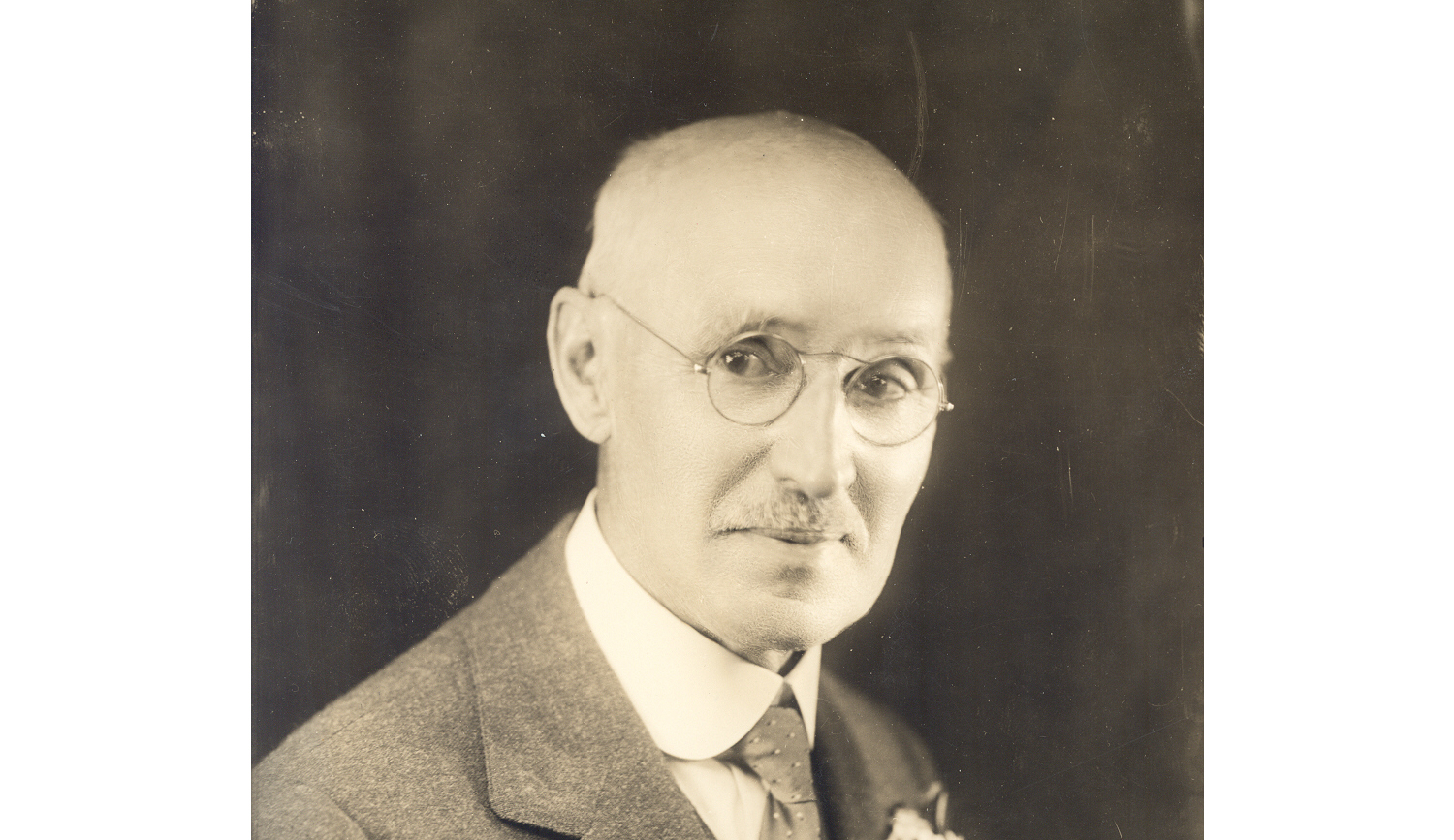

In today's world of high-speed, high-resolution digital photography, it seems hard to imagine that just seventy-five years ago, the act of photographing lightning strikes was an innovative, award-worthy achievement. The photographer who accomplished this amazing feat was William Jennings.

Who was William Jennings? A scientist? An artist? Both? What were his contributions to the photography of lightning?

A Word on Perspective

Born in England in November of 1860, William Nicholson Jennings would become one of America's premier photographers. He was a typist and a poet, a traveler and a scientist. Jennings had a scientific mind and a creative spirit, and he used his camera to photograph his time. He was determined to preserve it for the benefit of the future. Poetry, journals, scholarly articles and travel writings recorded Jennings' thoughts and experiences. His photography itself reveals his fascination with the written word. Viewers of Jennings' photographs of cityscapes will note that the photographer has made a conscious effort to capture the writing on billboards and street signs. Jennings believed that the inclusion of words would provide a framework for his photographs, giving his viewers a proper perspective.

Cross-Country

Jennings was an artist intent on producing quality work, as is seen in the text of the business cards he handed out in the 1900s:

If you have anything photographic you wish well done, call, write or

Telephone

Wm. N. Jennings

613 Heed Building 1213 and 1215 Filbert Streets, Philadelphia

Portraits at Studio or Home

Though Jennings focused more on his photography than on the state of his finances, the jobs he held were a key element of his success in photography. He started out as a stenographer and typed away for Wanamakers department store until he had a chance run-in with Pennsylvania Railroad real estate agent Robert Stiltson. The executive appeared in Wanamakers in urgent need of a typed letter, and Jennings earned his admiration by quickly typing exactly what he dictated. Shortly thereafter, Jennings began working as Stiltson's private secretary and was able to bargain for free railroad passes over the entire rail system. His personal and professional travels allowed him to photograph America, and his collection of scrapbooks and photographs are an invaluable portrait of the 19th and early 20th Century United States.

Unsinkable

Jennings' photography went from personal to practical to professional. Because of his photographic bent, the Pennsylvania Railroad began using his skills to survey construction sites and to track construction progress. This became common practice, and Jennings called it "Progressive Photography." He also mastered the art of photographing ships setting out for pleasure cruises. His talent enticed cruise lines to hire him to take professional photographs to be used for marketing purposes. His reputation in commercial photography earned him an invitation to take commercial photos aboard the Titanic, but prior commitments prevented him from accepting this offer. While doing work aboard the "Empress of Ireland" cruiseliner, Jennings learned of the sinking of the Titanic, having narrowly escaped the ill-fated voyage. Though his name surfaces on its passenger list, he never set foot on the decks of the White Star Line's "unsinkable" ship.

Elusive Electricity

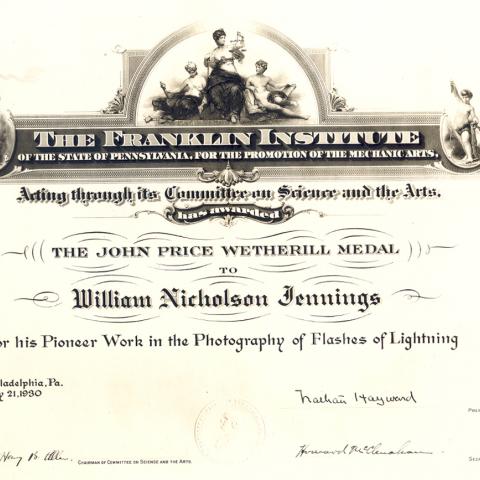

Perhaps his most difficult subjects to capture on film were the lightning bolts Jennings succeeded in photographing in 1882. The Franklin Institute recognized him for this feat with the Wetherill Medal in the 1930s, in honor of his work's contribution to the advancement of physical science. Jennings himself was a dedicated member of The Franklin Institute throughout his life, publishing articles in its Journal, giving presentations within its walls, and sitting on its Boards. When the Secretary of The Franklin Institute sent word to Jennings congratulating him on his achievement, he alluded to Jennings' commitment to The Franklin Institute itself as well as to the advancement of science: "How appropriate it seemed that we should try to pay honor to you."

Hot Off the Press

Jennings' pioneering work in photography coincided with the rise of print media and publication. The ability of scientists to publish their work sparked an intellectual discourse of sorts, as scientists from all over the globe began reading and responding in writing to the work of their colleagues. The publication of his work caused Jennings' name to circulate among well-known scientists of his day, and many of these men sent congratulatory notes in response to his articles and photographs. Joseph Leidy, the father of American vertebrate paleontology, said of Jennings' photography: "It is truly excellent, I had no idea such could be taken." A meaningful compliment from a man who unearthed the fossils of dinosaurs! John Tyndall, physicist and natural philosopher, sent warm thanks to Jennings upon receipt of one of his photographs: "I owe you, and offer you, my very best thanks for the exquisite photograph of lightning which you have been good enough to send me. Nothing so beautiful as your successes in this line ever came under my observation." Pulled from The Franklin Institute archives, an essay on "The Work of William N. Jennings in the Photography of Lightning" includes many detailed responses to Jennings' publication.

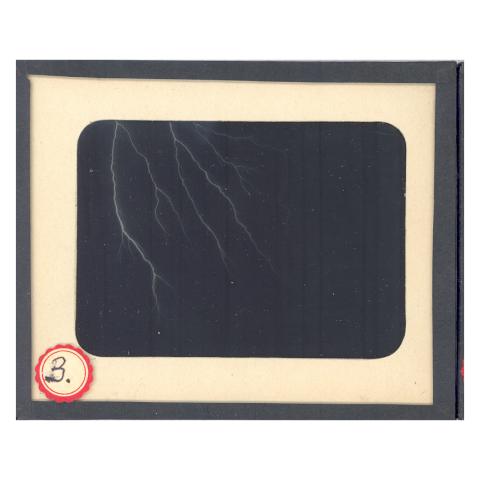

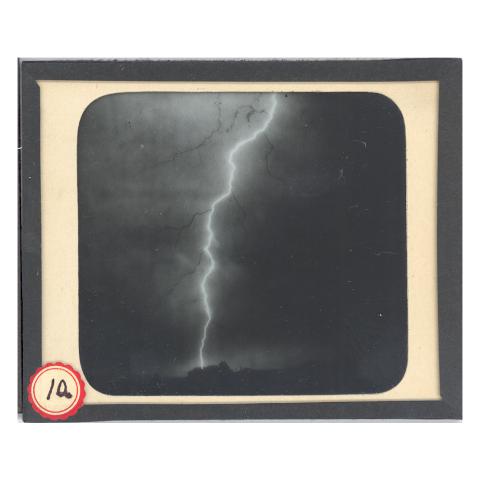

Zig-Zag Patterns

Jennings' success in photographing lightning paved the way for further research on the structure of lightning. Viewing his slides, scientists could discern distinct and varying patterns of electric discharge which result in the bolts of lightning that electrify the sky during thunderstorms. By all accounts, Jennings was inspired to attempt to photograph lightning after witnessing artistic renderings of lightning. He found that most artists depicted lightning as having a zig-zag shape, and set out to discover whether or not lightning did, in reality, have a zig-zag form. He determined that it did not, but on the way to this conclusion, he discovered many of the forms it does take. The Franklin Institute Awards Committee assembled a report outlining the different varieties of lightning Jennings photographed, accompanying each form with its corresponding photograph.

Unlike Any Other

Jennings was a nontraditional recipient of the Wetherill Medal. Most nominees for Franklin Institute awards are nominated for their own original inventions, but Jennings was not an inventor. He did make certain key adjustments to his camera in order to be able to photograph lightning, but he did not produce and patent an original invention. Though The Franklin Institute Committee on Science and the Arts did determine that it wanted to recognize Jennings' contributions to science, there was much debate as to what the appropriate reward would be. Two medals, the Longstreth Medal and the Wetherill Medal, were selected for the Committee to decide between. An original document outlines the requirements for both awards: "The Edward Longstreth Medal may be awarded for inventions or for meritorious improvements and developments in machines and mechanical processes;" "The John Price Wetherill Medal may be awarded for discovery or invention in the physical sciences, or for new and important combinations of principles of methods already known." The Wetherill Medal was ultimately chosen to recognize Jennings.

Committee member James Barnes summed up the reasoning behind this decision: "I think neither regulations governing the award of either silver medal fit the case exactly. However the Wetherill medal comes nearest to it, for Mr. Jennings discovered that lightning could be photographed which is a discovery in physical science."

Committee Chair Palmer called for a copy of the medal regulations to be sent out to all Committee Members. The Secretary complied, sending letters of instruction along with the regulations to each of them. Then the Secretary sent word to Palmer when each Committee Member had reached a decision.

Reaching New Heights

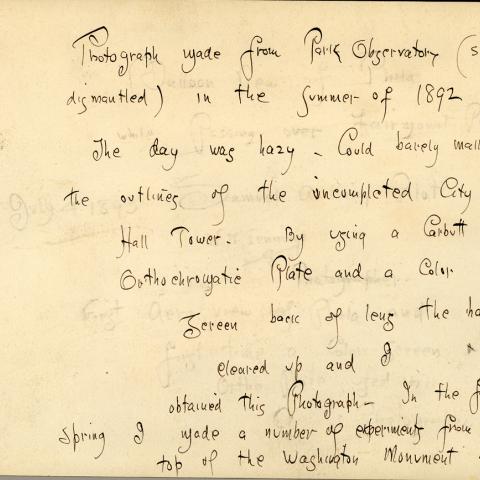

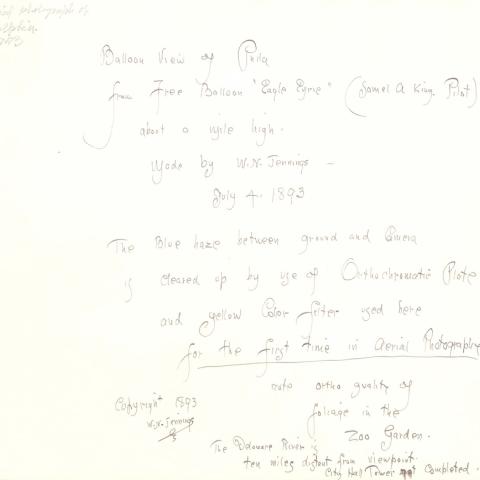

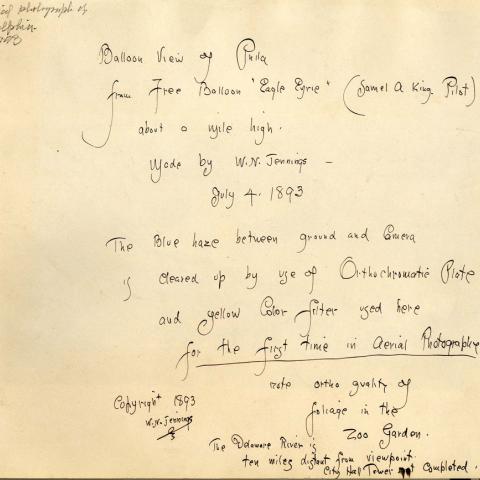

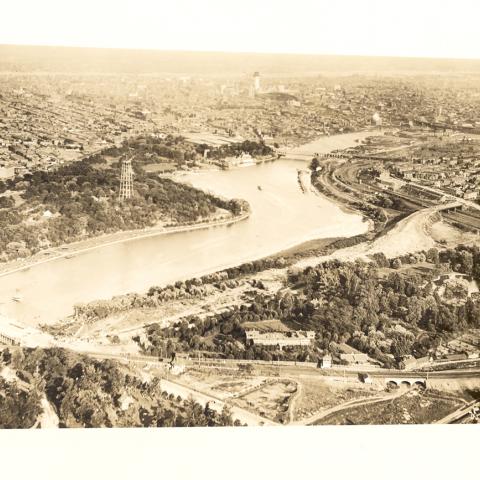

While Jennings did not invent the camera, he did make some significant modifications to its structure which enabled him to photograph lightning. Jennings' addition of a yellow color filter to his camera, along with the development of the hot air balloon, made it possible for the adventurous photographer to snap sharp images of lightning. The invention of the air balloon allowed Jennings and his camera to reach the optimal height for photographing lightning, and his use of a yellow color filter eliminated the blue haze that made ordinary photographs taken on an orthochromatic plate indistinct. Jennings' plate gave "good definition to the foliage in the Zoological Garden in the right foreground to the Delaware River ten miles away. The tower of City Hall in the middle distance is shown in an unfinished condition."

Lightning Striking

Jennings named the types of lightning he photographed according to their patterns of electric discharge.

-"Branched" discharge: named for the delicate "branches" created by its electric discharge.

-"Beaded" lightning: a photograph of this unique form of lightning was printed in the French publication "La Nature" (Nature) and entitled "the rosary."

-"Ribbon" lightning: in an article printed in the Journal of The Franklin Institute, Jennings explained that wind moving across the path of lightning in space produced a ribbon-like form of lightning.

-"Multiple flash": Jennings showed that lightning sometimes prepares a path for successive flashes.

-"Meandering" flash: form of lightning discharge that takes place from cloud to cloud, usually occurring at the end of a storm.

-Subject to debate: this photo captures the phenomenon of a brilliant main flash with dark side branches, the cause of which has been given a great deal of discussion.

Something to Prove

Jennings set out to prove that the wind was the cause of the ribbon effect in a laboratory of the University of Pennsylvania, under the direction of Professor Arthur Goodspeed. To test Jennings' theory, the two scientists blew a blast of air across the direction of a single spark from an induction coil, resulting in the image shown here:

In a letter to Franklin Institute Secretary Hoadley, Jennings claimed that the "Ribbon Effect" was his own original observation.

Jennings also proved that a lightning flash does not confine itself to one plane. In order to demonstrate this fact, he placed two similar cameras one-hundred feet apart, and succeeded in obtaining two negatives of the same discharge.

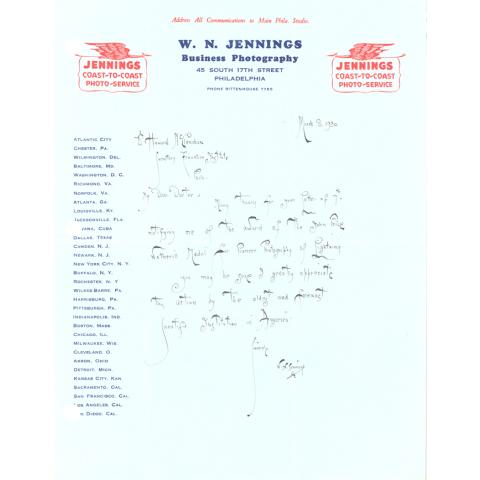

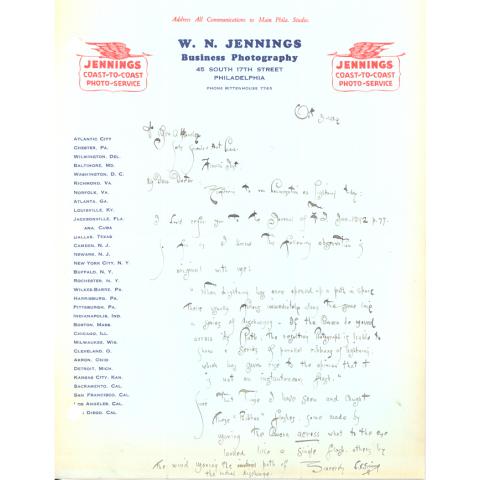

Transcription of Jennings to Hoadley, 10/3/1929:

My Dear Doctor:

Referring to our conversation on lightning today:

I would refer you to the Journal of the F.I. Jan. 1892 p. 77

So far as I know the following observation is original with me:

"When lightning has once opened up a path in space there usually follows immediately along the same line a series of discharges. If the camera be moved across its path, the resulting photograph is liable to show a series of parallel ribbons of lightning, which has given rise to the opinion that it is not an instantaneous flash."

Since that time I have seen and caught these "ribbon" flashes, some made by moving the camera across what to the eye looked like a single flashes, others by the wind moving the path of the original discharge.

Sincerely,

W.N. Jennings

Be Our Guest

Goodspeed acted as a lab partner, mentor, and friend to Jennings. Jennings' high regard for Goodspeed is seen in the following exchange of letters, in which Jennings specifically requests that Dr. Goodspeed be invited to his medal day exercises: "I should very much like to show my old friend D. Arthur W. Goodspeed how much I appreciate his encouragement and assistance in my early Photo Electric work by having him as my special guest on that occasion."

One of Their Own

William N. Jennings was himself a Member of The Franklin Institute Committee on Science and the Arts, the Committee responsible for the review of scientists and inventors nominated for awards. The regulations of the Committee stated that "the Committee could not consider the work of any Member of the Committee unless directed to do so by The Franklin Institute or the Board of Managers." Secretary of The Franklin Institute George A. Hoadley moved that the Board of Managers consider Jennings for award, and a letter confirms that his movement was placed before that Board.

Neat lines of carefully-formed calligraphy on his certificate of award recognize Jennings for his "pioneer work in the photography of flashes of lightning."

Speak Now or Forever Hold Your Peace

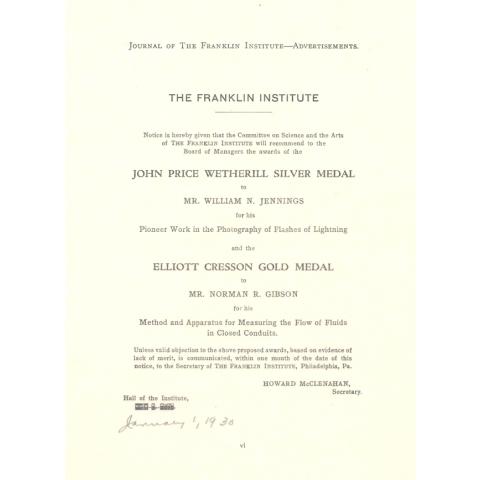

The Franklin Institute recognized William N. Jennings for his "pioneer work in the photography of flashes of lightning" with the John Price Wetherill Silver Medal. An advertisement placed in the January 1930 edition of the Journal of The Franklin Institute informed readers of Jennings' pending receipt of this award. The advertisement both declared Jennings' accomplishments and called for objections to his receipt of the Wetherill Medal, instructing readers to communicate any objections to the Secretary of The Franklin Institute "within one month of the date of this notice."

A Debatable First

Due to the uncommon nature of Jennings' scientific achievement, there was much debate as to what exactly he should be rewarded for. He was not an inventor, but his work nonetheless made a significant impact on the study of physical science. A letter from Franklin Institute Secretary Hoadley questioned Jennings' primacy in photographing lightning: was he really the first to achieve this feat? Many documents in Jennings' case file record the discussion that went back and forth among the members regarding this question. Ultimately, the Committee on Science and the Arts was unable to verify that Jennings was the first photographer of lightning. The final Committee report on Jennings records that "The Institute has been unable to find that any photograph was taken prior to Mr. Jennings' photograph in 1882."

Documents record the correspondence between Secretary Hoadley, and Committee members Dorsey and Humphreys. Both Dorsey and Humphreys are requested to investigate primacy in the photographing of lightning, though the letters suggest that only Humphreys takes this task seriously. Hoadley's letter to Dorsey tersely notes that Dorsey has "never made an investigation," while Humphreys' letter from the Secretary is obliging and expresses thanks for his "courteous cooperation."

Pleased to Inform You

Jennings was notified of his recommendation for the Wetherill Medal and the placement of the advertisement in the Journal. After a month elapsed with no objection to his receipt of the award, congratulatory remarks were sent from The Franklin Institute. In a letter to the Secretary of The Franklin Institute after notification of the Committee's decision to award him the Wetherill Medal, Jennings expressed his warm thanks: "You may be sure I greatly appreciate this action by the oldest and foremost scientific institution in America."

Credits

The William Jennings project is made possible by support from The Barra Foundation and Unisys.

This website is the effort of an in-house special project team at The Franklin Institute, working under the direction of Carol Parssinen, Senior Vice-President for the Center for Innovation in Science Learning, and Bo Hammer, Vice-President for The Franklin Center.

Special project team members from the Educational Technology department are:

Karen Elinich, Barbara Holberg, Margaret Ennis, and Natasha Fedder.

Special project team members from the Curatorial department are:

John Alviti and Andre Pollack.

The project's Advisory Board Members are:

Ruth Schwartz-Cowan, Leonard Rosenfeld, Nathan Ensmenger, and Susan Yoon.

Read the Committee on Science and the Arts Report on William Jennings work in photographing lightning.